Leading with humility

Why being humble is a trait that's too overlooked and underrated

"I am going to begin with the value of humility, and by admitting that I have much to be humble about.... Over my long career, I have made many mistakes, and I will make more, but I commit to admitting them openly, to correcting them quickly, and always learning from them." - Mark Carney's election victory speech, 28th April 2025

When Canada elected Mark Carney as its Prime Minister on Monday night, the word 'humility' was mentioned six times. I paid attention to this because it's a word that always makes my ears perk up.

I notice the word humility because it's a trait that I don't often hear about but deeply value, as it's how I would describe the most formative leadership role model in my life: my dad.

As someone consistently recognized as of the Royal Canadian Air Force's most skilled aviators, my dad (who died when I was 24) had more than enough reasons to be insufferably boastful about his accomplishments. But, he just wasn't– I mostly learned of his accomplishments second hand, through other people. Any stories he told me directly were either funny ones (like being caught by Queen Elizabeth roaming the hallways of Buckingham Palace in his swimming trunks) or they were rooted in facts and figures, with very little elaboration or pride. My dad didn't lack confidence; He just couldn't stomach people who boast or brag. In other words, he had an extremely high regard for humility.

Here's something my brother wrote this about our dad recently:

"While he hinted at his accomplishments, their reality was concealed by his humility. 'Fame' was not something he was ever troubled with or sought."

I've been thinking about what humility means, in politics, in leadership, but mostly in the intertwined story of my dad and myself.

Humility is underrated and misunderstood

Many of the leaders I've worked for or with could be described as humble, but I rarely (or never) hear them self-identify this way. Why?

Perhaps its because the common definitions for humility feel a bit off, like this one:

Humility (noun) – the feeling or attitude that you have no special importance that makes you better than others; lack of pride - Cambridge online dictionary, American definition

Humility is often positioned as the opposite to pride, making it a trait that only egoless monks can aspire to. But pride in one's successes when fairly earned can be a foundation for confidence and self-esteem, which can (and I think, should) exist alongside humility.

If we're going to embrace humility as important, we have to begin to see it as something that can co-exist with a healthy, reasonable amount of pride. This might look like:

- Meaningfully recognizing the contributions of others when accepting praise

- Acknowledging the perspectives of others as equally important when sharing your own perspective

- Being open to critics and honest about shortcomings when sharing successes

But humility isn't effective as a standalone trait

Most humans would agree that humility is a positive trait to have in leaders - we want the people in charge to be honest and open to talking about faults. It feels authentic and builds trust.

And yet, it can be hard to have confidence in someone who says, "this is new to me," "I don't have the answers" or - my personal pet peeve - "we're building the plane while we're flying it." Those phrases might feel humble and authentic, but they lack confidence. Nobody would feel safe flying on a half-built plane.

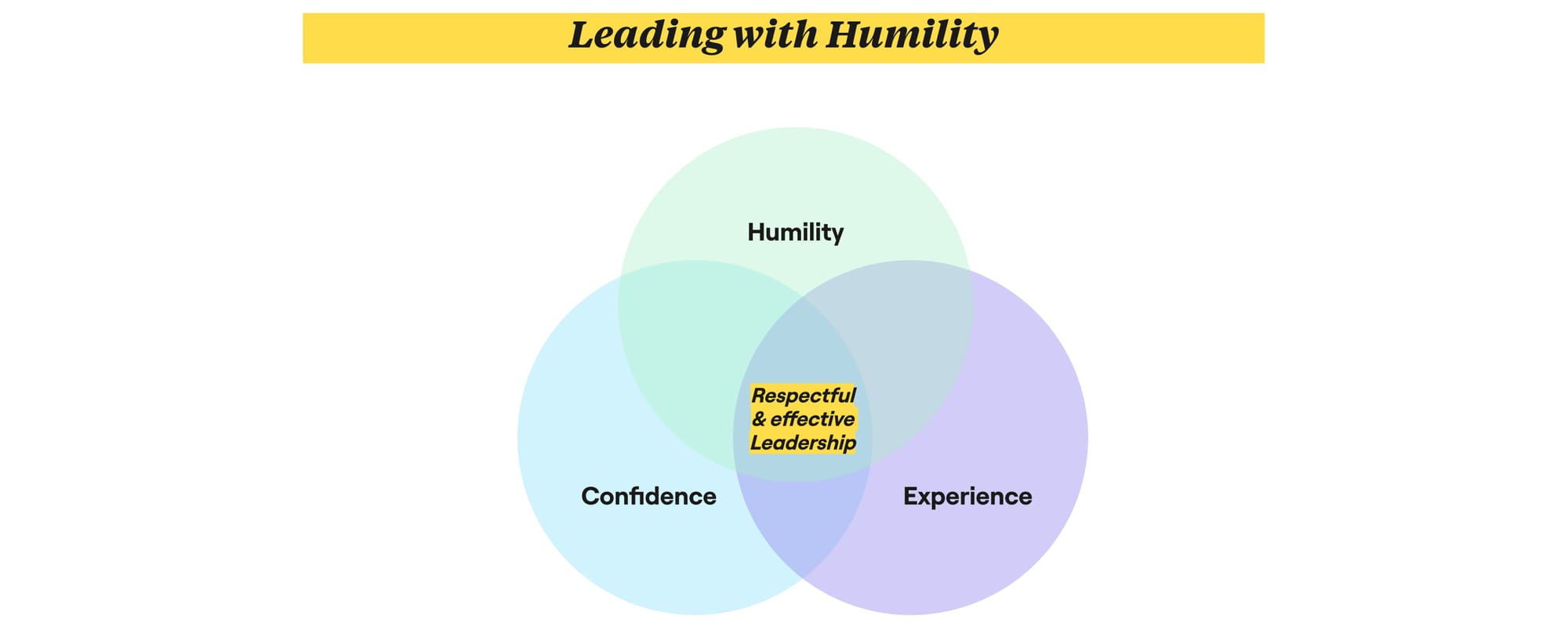

To be an effective leader, humility must be combined and balanced with confidence and experience.

Imagine a workplace or team going through a time of change or uncertainty:

- A leader who lacks humility says, "things are difficult and I'm the only one who knows what to do."

- A leader who lacks confidence say, "this is pretty bad. What do you think I should do?"

- A leader who lacks both says, "this is too complex to fix and I can't do anything about it so stop complaining, you're making things worse."

None of those responses are very reassuring or empowering, because neither humility nor confidence are inspiring on their own. Here I've attempted to map out what the relationship between those two concepts looks like in leaders:

But a leader with a good balance of humility and confidence (plus the experience to back that confidence up) might say something like, "I hear you and I understand how uncertain you feel. But I've done this before and I'm not worried. I'm going to share my plan with you and I want your honest feedback."

This is the kind of leader people want - someone who acknowledges and cares about your fears but also comes across as calm and and steady and capable. The kind of leader that Mark Carney is hoping to be, and the kind of leader (and pilot) my dad was.

Why isn't humility considered a core value in the workplace?

Have I managed to convince you that humility is a trait to be valued yet? If so, maybe we should talk about whether it could be a requirement for all higher leadership roles, in the private sector, as well as politics and government.

Here's an interesting finding:

"A research team from Arizona State University [found] that humble CEOS (defined as those who recognized their own strengths and weaknesses and appreciated the strengths and contributions of others) often created better financial returns for their companies" - After You: Humility As A Core Leadership Skill

That said, I have a hard time seeing humility making it onto any executive job profiles, for a few reasons:

- Traditional job interviews (at any level) favour candidates who are comfortable with boasting about their own achievements

- Hierarchical org structures put a monetary value on some types of people over others, sending the message that everyone is not of equal importance

- Executive positions put a high priority on quick thinking and decisiveness, which can be challenging for people very high in humility, especially when they value input from others

- The demands of a leadership role favour certain personality types and personal circumstances over others

- Admitting mistakes and accepting criticism is often viewed as shameful and a sign of weakness in corporate and executive circles

- Performance measurement processes encourage employees to collect their stories of success

- Even if we did agree humility was important, it's difficult to measure, and I'm not sure if it can be taught

But one can dream: What would our organizational culture look like if we hired for experience, confidence and humility, instead of prioritizing only the first two?

What would our society look like if this was something we all agreed was valuable?

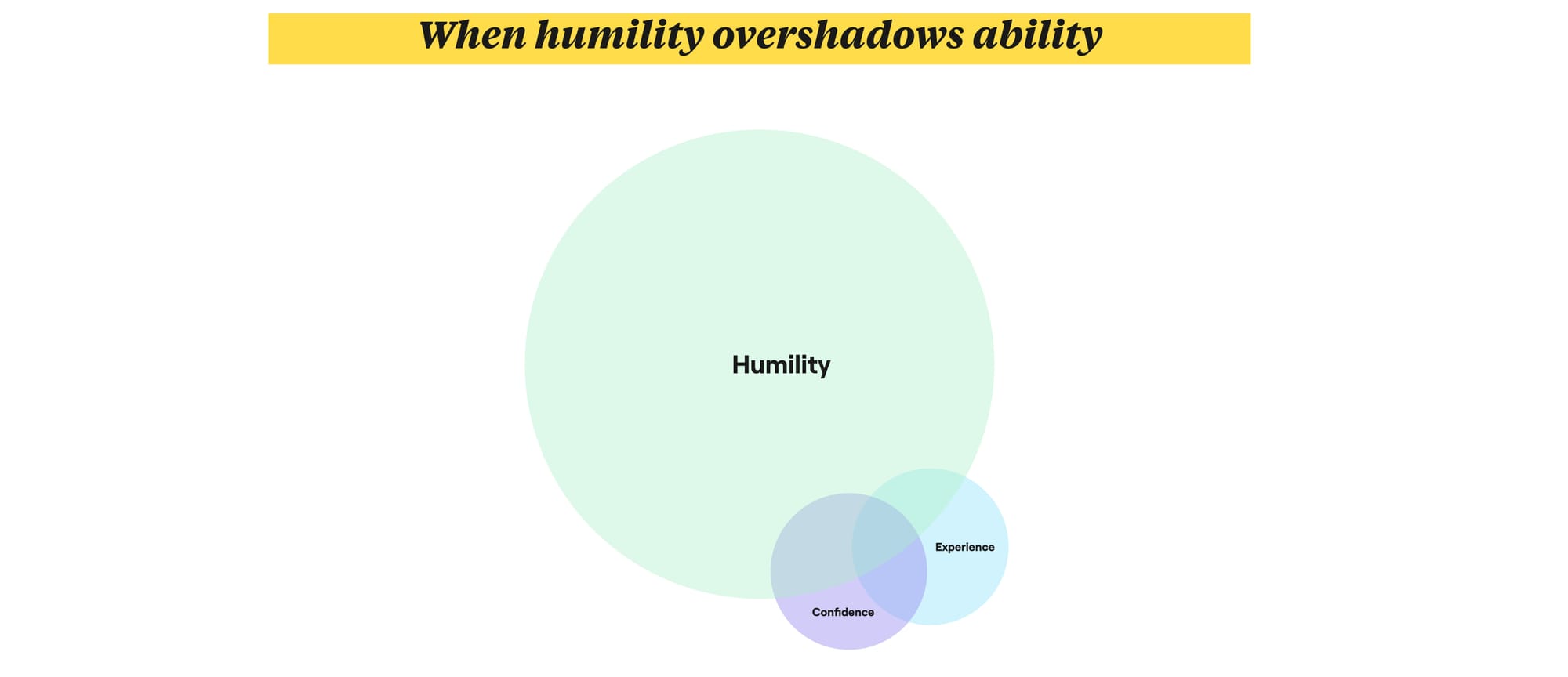

It's possible to over-value humility, too

Humility is something I deeply value, but in reflecting on my relationship with it, I think it can be taken too far. It may look like this:

Too much humility can overshadow confidence and ability. I sometimes worry I take humility too far. I'm self-deprecating. I let insecurities overshadow my achievements. I overthink things to death and defer decisions to others. I make recommendations but I'm hesitant to call the shots.

I see this a lot in my field of work, as a human-centred designer. Service design and user research are all about questioning everything, sharing power, and following the lead that the users and findings take us. It's easy to be humble in this work, because it goes against our training to steer things in a certain direction, until we have input from everything. It's more of a challenge to be the calm, reassuring pilot when the destination is unclear. Yes, it comes back to using evidence and our research skills to build confidence in decisions– but when our practice isn't well-understood by those we work with, the process may seem too slow and uncertain to assure confidence.

Too much humility can undermine self-esteem and self-worth. As a parent, I want my children to value humility as I do. But I also want them to grow into humans who believe in themselves and their abilities. I want them to be proud of themselves.

I don't know how my dad felt about himself, or how healthy his self-esteem was as a person who constantly downplayed his own accomplishments. I have a hunch that as a handsome and charismatic white man with a cool and important job, he had enough people singing his praises. He probably didn't need to be his own cheerleader.

But when the younger version of myself, like him, downplayed every success I had, I believed her. It took many years, a lot of evidence, and some wonderful friends, colleagues and bosses to even begin to bring me around to the idea that I may have something of value to offer the world. I genuinely don't begrudge my dad for this - I still see humility as one of my strengths - but it is something I'm keenly aware of as I help my own children figure out who they are.

And finally, too much humility makes it hard for people to really know you. For the past few years, a friend of my dad's has been working to get him recognized in the Canadian Aviation Hall of Fame. While doing some deep research for the submission, my brother has been coming across stories and facts that none of us knew before. And I learned that many of the aviation books in my dad's bookshelf weren't just there because they interested him; they were there because he was in them.

I knew my dad very well, but in learning more about his life I realize I only really knew one version well: the sometimes silly, sometimes serious, usually fairly jolly homebody who occasionally flew planes and played golf as much as he could, but mostly spent his time ferrying my brother and I around the city, delighted at the chance to be a dad late in life (though not delighted at all the traffic, a typical grumpy dad through and through.) I'm so lucky I got to be one of the few people who saw that side of him.

The other version– celebrated aviator, retired general, one-time royal equerry, a fair and down-to-earth boss who stood up for what he believed in and advocated for people when they needed it – I mostly learned about second hand, because that's who he was, and I'm ok with that. Still, if I had the chance to spend another day with him, you better believe I would ask a million questions.

My brother wrote this of my dad which I think summed him up perfectly:

"He never saw the need to make a big fuss out of his story....Having lived his dream, he was content in the memories and satisfied with a job well done. One of the most understated people I will ever know."

I'll wrap this up by saying this:

Being grounded in confident humility = the vibe we all need right now

Maybe I'm a naive optimist, but hearing the Prime Minister of Canada place value on humility felt like a small but significant positive shift in political discourse of our country, and perhaps society as a whole. I don't know about you but I am so ready for this shift, and this small word, repeated a few times, filled me with hope, if even just for a moment.

I really hope it catches on.

--

The TL;DR ("too long, didn't read") version

I love summaries so here's one for this very-long blog post:

- Humility is misunderstood – it's not the opposite of confidence, pride or uncertainty. It's actually about recognizing the importance of others while being open and honest about both success and shortcomings.

- People who are high in humility are approachable, honest and supportive, and have the ability to build trust and bring people together in powerful ways. They welcome critics and value openness. They make people feel heard, valued, and safe.

- Humility is underrated in leadership; leaders who have humility, confidence and experience are trusted and trustworthy; respectful and respected. But traditional hiring processes, particularly at leadership levels, usually don't put a high value on humility.

- Like anything, humility is a balance. Too much humility can undermine your ability and self-worth, and make it challenging for people to know you fully.

End note: Though he won't read it and can't give his permission, I still feel compelled to say that my dad would probably not have consented to be written about here, partially for reasons of a personal preference for humility that should be obvious by now, but mostly because he would not enjoy being mentioned in an article that also favourably mentioned the Liberal Party, a political party that he considered one of his greatest lifelong foes. If anything could cause him to come back to haunt me for the rest of the my days, it would be this, so I shall say here: Sorry, dad.

Comments ()