What 'efficiency' looks like ... and doesn't

The word 'efficiency' is everywhere in government right now. But what does it actually mean? The concept feels fuzzy to me—poorly defined and open to interpretation.

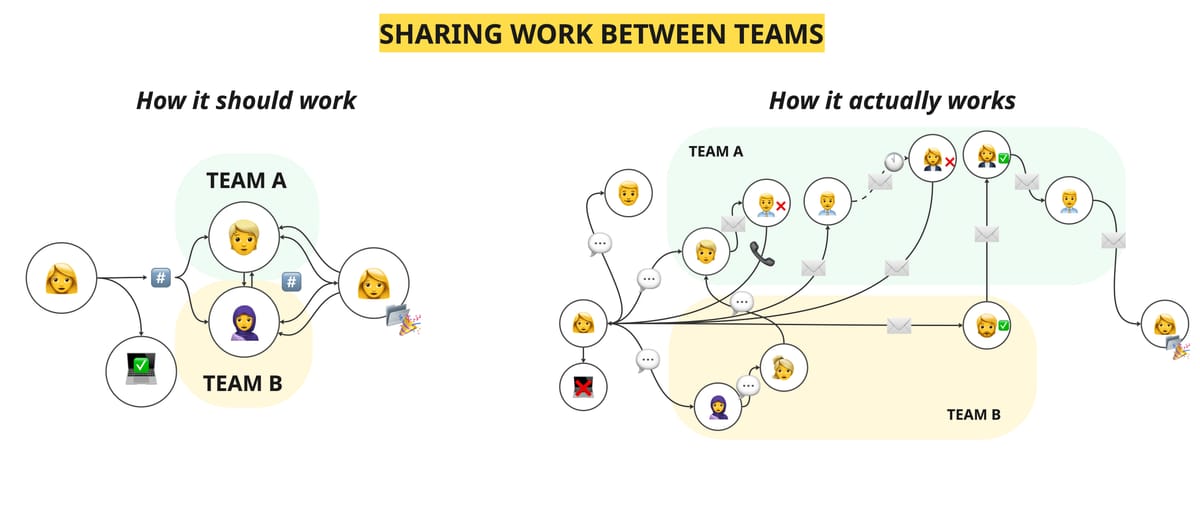

So, I decided to sketch it out and visualize what it looks like in my work.

As a service designer, I spend a lot of time digging into all the previous work that's been done on the particular service or initiative I'm looking at. This is incredibly important for learning the context of the work, but it's also a huge determinant of the timeline and efficiency of the project: If I can build off of past learnings rather than starting from scratch, I can save weeks or sometimes months of work.

My ability to access previous work in an efficient and straightforward way can make or break a project. So let's look at two real-life examples of how that's worked in previous projects.

Two important notes before I start: 1) in both examples, the previous work did not contain any sensitive or classified information, and 2) I'm not going to name either org because it's irrelevant, but I will say they are both government orgs. You may be able to guess one of them.

--

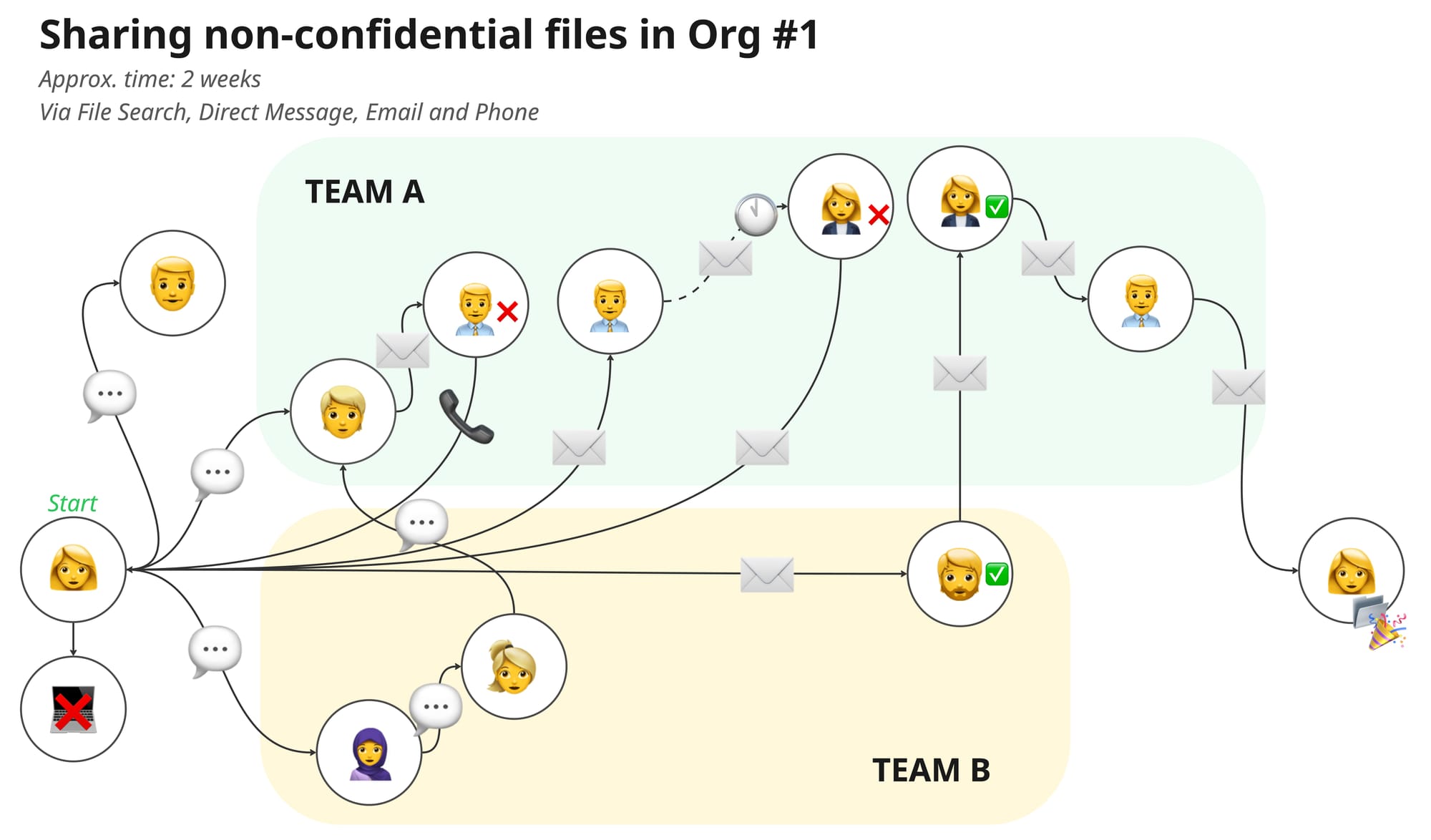

Case study: Accessing files in Organization #1

The context: I was tasked with building a journey map for a government service delivered by Team B. A few days into my research, I learned from a random conversation that this work had already been done a few years ago by Team A. I searched the folders I had access to, but I found nothing so I asked teams A and B for access so I could save time and avoid duplicating work.

Here's a very basic diagram of that process:

That visual is kind of confusing, so here's the overview:

- Zero search results on 5 different systems with dozens of keywords

- 8 people involved and 15 separate communication threads (direct messaging, email and phone)

- 3 sets of approvals from directors and senior directors

- A review of a 4-year-old sharing agreement for the original project

- 2.5 week delay to the project while I waited on all of the above

- Reminder: these documents contained zero confidential or classified information

--

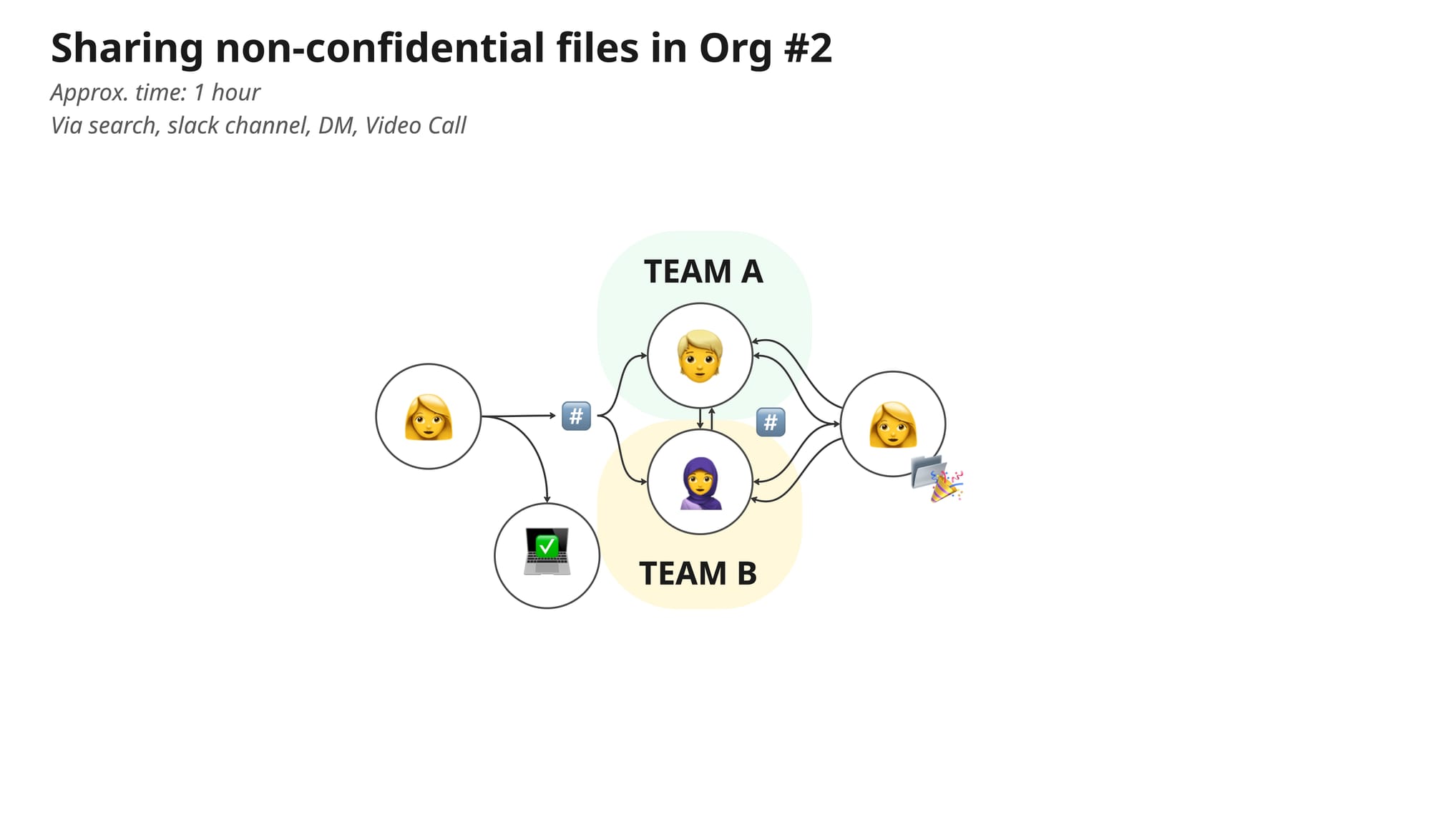

Case Study: Accessing files in Organization #2

The context: I was mapping the user journey of using a particular component (built by team A) that was common across multiple services and products. My own team hadn't researched this yet, but I wondered if someone from another team had. Here's how that went:

The overview:

- A google search led to public blog posts, from Team A and also a team that had used it (Team B)

- An internal file search led to Team A's user research folder with several detailed research reports that I was able to access

- I put a post on an open cross-gov slack channel which yielded links to another research report, and led to an open conversation with Team A and Team B, who had used it in their own service build. This resulted in an ongoing collaboration with team A to share learnings and expand on their previous work

- Zero approvals and no delays

--

The differences between Org 1 and Org 2

It's pretty obvious that sharing information in org 2 was much more efficient. But why? I see five main differences:

| Organization 1 | Organization 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Trust | ❌ Employees not trusted to make decisions about sharing work; requires multiple layers of approval | ✅ Employees trusted and empowered to make low-risk sharing decisions without manager or director approval |

| 2. Clarity | ❌ Sharing process and levels of document classification aren't clear, so all work is treated as very sensitive | ✅ Levels of classification are clear, so people know what info can be shared and what needs more diligence |

| 3. Transparency | ❌ Work is hidden from view, internally and externally. | ✅ Work is shared internally in safe ways. Appropriate details shared with the public. |

| 4. Findability | ❌ Finding information depends on word of mouth; it can't be found without human intervention | ✅ People can find information on their own, without asking for help |

| 5. Efficient Communication | ❌ Communication happens across multiple channels, in small, closed groups with hand-selected individuals | ✅ Communication happens on one platform and often in open channels where any employee in that channel can benefit or contribute |

Reflecting on these five aspects lead me to this thought:

Perhaps 'efficiency' is more about culture than process

Efficiency is typically seen as a process problem: too much red tape, bureaucracy, administrative burden, sludge, whatever you want to call it.

But processes are made by people, and people are shaped by the culture they exist in. This culture is expressed through the values and rules, both explicit and unwritten.

- Openness is largely cultural

- Employees feeling trusted and empowered is largely cultural

- A mindset of shared ownership and transparency is largely cultural

Many of the processes that we experience (approvals, gatekeeping policies, inefficient communication patterns) come from long-standing cultural mindsets that continue to be automatically reinforced, even when we can see they are no longer serving us.

But 'culture' sounds fuzzy and big and difficult to change, so it just seems easier to focus on the processes as standalone issues, rather than question and reflect on the systemic culture that created them.

And yet, I think most of us know that nothing will ever really change if we don't think big.

An culture of efficiency is possible, if we are willing to do the work

Having experiences both types of organizations, it's challenging when I hear things like, "that's just how it is, we can't change things," because I know it's not true. Org #2 is a government organization with all the same rules as Org #1 and they successfully shifted toward to a more efficient culture. I know many other public sector teams that have done this too.

Org #2 did this by:

- Reinforcing efficient cultural mindsets through slogans, stickers, posters, lanyards and other materials (such as, "work in the open, it makes things better")

- Trusting and empowering staff to make reasonable decisions without leader intervention

- Ensuring IT and documentation policies allowed for safe sharing and findability

- Prioritizing public communications (blogs, events, demos, showcases, podcasts) so people didn't need to ask around for information

- Supporting and funding cross-government collaboration: working groups, communities of practice and sharing platforms like Slack

- Making it part of the job description - open sharing was part of team mandates, roadmaps, sprint planning and even performance reviews.

True cultural shifts are a lot of work, and they can only happen top down and bottom up.

But as the saying goes, the second best time to plan a tree is now, so perhaps we should start digging.

Comments ()