What evidence misses

Disclaimer: I'm sharing these thoughts only as an individual. What I say isn't a reflection (or assessment) of my employer in any way. I'm not involved in or affected by the decision or story mentioned, and my interest in this is solely as a member of the same community as this family.

July 18th update: the outcome of the media story I mention in this blog post has changed significantly since I wrote this. But I think these musings on evidence and lived experience are still relevant so I'm keeping it up

--

Charleigh, a 9-year-old girl in my daughter's class at school, has been in the news lately and not for happy reasons. Her story is a heartbreaking and stark reminder of the impact of decisions on families and communities.

Obviously this story is not about me in any way, and it's not my intention to take any attention away from it. This blog post isn't about that. But like many in our community I've been feeling shaken and confused and disheartened by the situation.

The anxiety of feeling helpless and hopeless is something I usually work through in writing. Sometimes I will do that publicly. So, that is what this blog post is about.

--

I keep ruminating on these questions:

Why are some types of information considered more worthy than others?

Why are some voices listened to over others?

Who decided that?

Who benefits from it, and who doesn't?

--

In the professional circles I am part of, we talk a lot about 'evidence-based decisions' as a way to get to outcomes that are fairer, less risky, more concrete. Decisions that are impartial, objective, not swayed by whims and opinions and emotions. I like this approach. It makes decisions feel legitimate and valid.

And yet.

I can't ignore that it doesn't feel quite right when evidence alone determines human outcomes. When a 'panel' can make a human decision with data only, without experiencing the humaness of that person and those around them.

So I wonder: have we got it right?

What are we missing?

--

Evidence is usually code for 'data and facts' and these can tell some of a story but not the whole one.

Because, we all know well that 'data' can be an unreliable narrator: imperfectly collected, incomplete, interpreted incorrectly, or sometimes even cherry-picked to prove a point

But also: Data and evidence don't feel hope,

or comfort,

or grief,

or despair,

or hope.

They don't sit at someone's hospital bed in tears, or feel the heart surge of a child's laughter.

Yet, all of those things are still real and true, whether data captures it or not.

As far as I know, data doesn't explain the placebo effect, or how hope alone can change healthcare outcomes. It doesn't capture relationships or personality or connection or what people are feeling and why. It doesn't tell us why things that match up on paper don't work together well in real life, and vice versa.

It can help to predict but with varying degrees of certainty. Sometimes that certainty is overstated or exaggerated.

The thing is, even total certainty feels irrelevant, because humans don't experience evidence or data or facts.

They experience life and love and emotion and pain and connection and hope and despair. All things a dataset can't measure or interpret or reflect or predict with total accuracy.

So, what are we missing when we look at data alone?

My hunch is: everything.

--

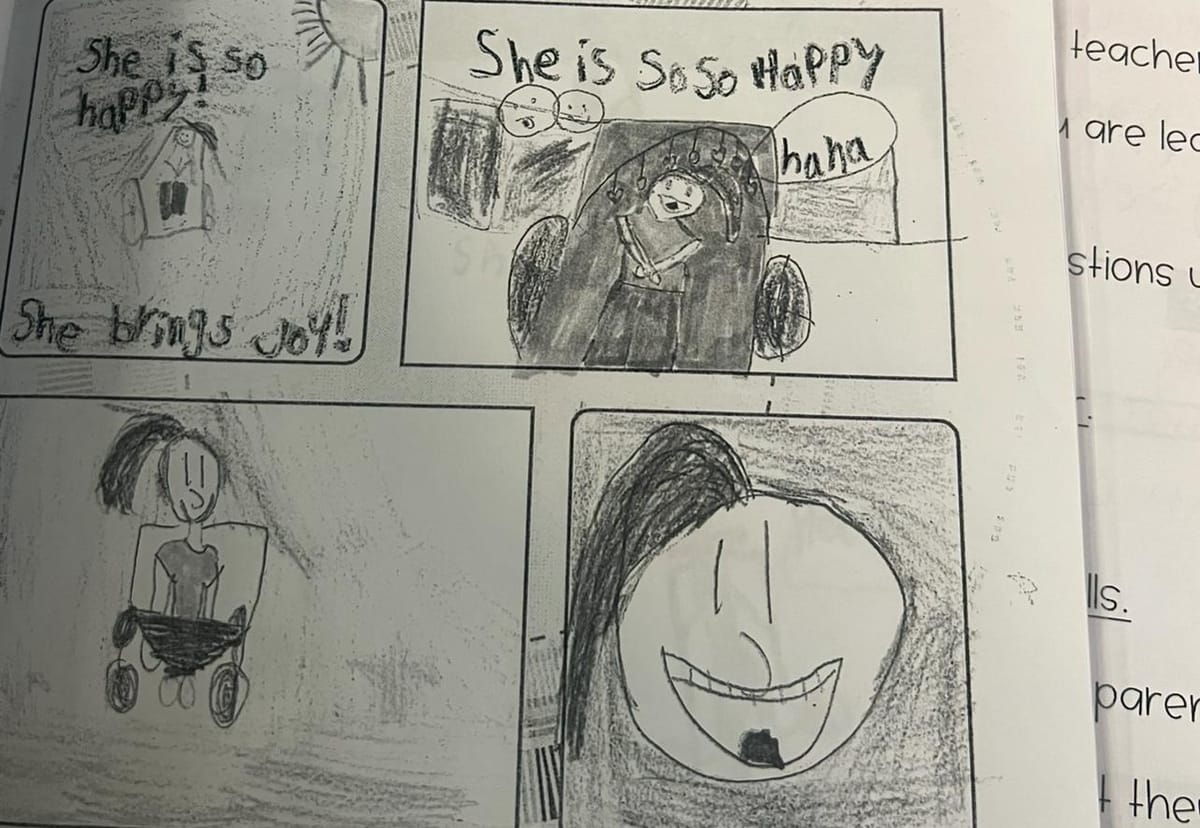

When I think about evidence, my mind keeps going to this book my daughter's class created about Charleigh:

"She brings kindness and joy"

"She's always laughing"

"She is so, so happy"

A hundred years from now, historians and anthropologists might call something like this "an artifact," a rich piece of 'evidence' that tells a past-tense story of a child beloved by the people around her, who was an active participant in her community and school (even if 'data' might suggest otherwise.) Artifacts fill in the critical pieces that census data and population statistics and test results cannot. They tell the actual human story. That's why they are displayed in museums.

But in the present moment, right now, this is not considered evidence. Why? That it comes from children usually makes it automatically invalid (which itself feels kind of wrong.) But several times in the past I've had decision-makers brush off any first person accounts I surface in my research by labelling them "anecdotal." Anything too personal or too emotional is quickly dismissed as a subjective experience or opinion that doesn't accurately represent the "truth" of the situation.

But, what is 'truth'?

Who's truth is it?

Who's truth matters more?

And who decided that?

Are the voices and experiences of people in and around and affected by a decision considered part of 'the evidence'?

I already know the answer to that, so here's the real question that keeps me up at night:

What is it going to take to get the humanity and lived experiences of real people deemed valid and important and true? And what can I do about it? What can we all do about it?

Advocating for this kind of change can feel slow. Mostly that's ok, but sometimes it's not. Sometimes it's urgent. Sometimes it's life or death.

And that's what keeps me up at night.

--

But: ruminating is only helpful in small doses. What helps more is to take action. So:

Advice for when you feel helpless

- Look up ways to support a cause (fundraise, sign petitions, volunteer)

- Write to your MLA, MP, local council, and follow up when you don't hear back (which will happen, a lot)

- Share and elevate the stories/issues you care about on social media (apparently likes, comments and saves all help)

- Connect with people to talk about it

- Write to the media

- Get outside

- Look for small ways to advocate in the everyday interactions you see

- Write about it (see above)

--

If you've been affected by the story of my daughter's classmate and want to help, her name is Charleigh Pollock and you can donate to her GoFundMe or follow her family on social media.

And if Charleigh's family happen to read this: I am so, so sorry. I wish there was more we all could do to help you.

Comments ()